HIDE CAPTION

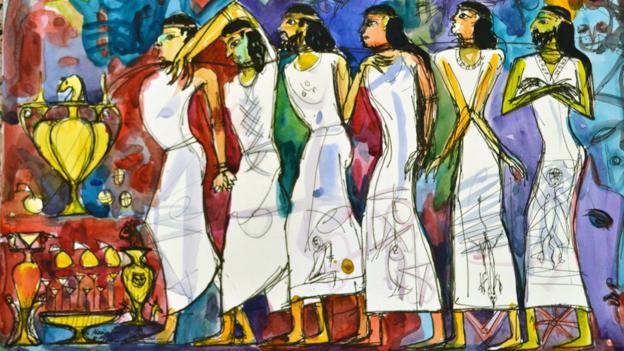

- Culture clash

- The art of ancient Egypt is a huge influence on the work of Alaa Awad, a prominent member of the country’s new generation of street artists. (Alaa Awad)

Astonishing work has been emerging from a new generation of Egyptian street artists. Influenced by ancient culture and contemporary politics, they are delivering potent messages of protest. Alastair Sooke surveys the scene and meets a major player.

More than two years after protesters toppled Hosni Mubarak, Cairo is still ablaze with fiery visual reminders of Egypt’s revolution. On the edge of Tahrir Square – the nerve centre of dissent – the burned-out tower block that once housed the headquarters of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party stands blackened and empty. It forms a jarring juxtaposition with the coral-pink walls of the Egyptian Museum, the dusty storehouse of the country’s most precious antiquities, next door.

Around the corner, there is a different kind of monument to the revolution. Mohamed Mahmoud Street – which intersects with Tahrir Square from the east – is as colourful and vibrant as the sombre hulk of the NDP building is charred. Almost every square centimetre of the walls that flank the street has been covered with bright, cacophonous paint. These murals are some of the best examples of the inimitable street art movement that has flourished since the protests against Mubarak began.

“There was very little street art in Egypt before the revolution,” says Mia Gröndahl, a writer and photographer who has lived in Cairo since 2001, and whose book Revolution Graffiti: Street Art of the New Egypt was published in the UK last month. “So few pieces, in fact, that people weren’t aware of it. But Egypt had the artists waiting to come out of the closet and express themselves honestly and politically.”

Most of these artists were forged in the fire of the 18-day demonstrations against Mubarak in early 2011, when at least 846 people were killed. Emboldened by the ferocity of the protesters, several artists started painting slogans and murals commenting upon the tumultuous events that were convulsing their country. While other young protesters hurled bricks, Egypt’s fledgling street artists picked up paintbrushes and spray cans. “By the summer of 2011,” Gröndahl writes in her book, “people [had] started to talk about the walls of Egypt being under an ‘art attack’.”

Mad graffiti weekend

Two years ago this month, during a collaborative event known as the “Mad Graffiti Weekend”, Ganzeer, a graphic designer, created an unforgettable stencilled mural of a large tank aiming its cannon at a boy on a bicycle who is balancing a tray of bread upon his head. Over time, the mural was added to, retouched, painted over and defaced, in response to events such as the “Maspero Massacre” of October 2011, when security forces and the army killed more than 25 Egyptian Copts who were peacefully protesting about the destruction of a church.

One memorable character to appear on the wall – a pot-bellied panda bear with drooping shoulders and a melancholy expression – has disappeared beneath subsequent layers of paint. Despite this, though, the Sad Panda, a resigned witness to ongoing mayhem that has since appeared on various walls around Cairo, has become one of the most recognisable visual motifs in the country’s new lexicon of street art. His negative body language offers a kind of pacifist rebuke to the violence and uncertainty that have engulfed Egypt since 2011.

“People in Egypt love street art,” Gröndahl tells me. “There is an old heritage of expressing yourself in images here, so they are no strangers to it. It has become an integrated part of the continuous struggle for freedom. The graffiti reminds people that the revolution isn’t over yet.”

Revolution Graffiti documents the urgency and self-confidence of contemporary Egyptian street art. Most of the images reproduced in the book make the work of celebrated British graffiti artists such as Banksy appear insipid by comparison. Street art, by definition, should be by the people, for the people: in Egypt it has proved a strident yet eloquent instrument of protest.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου